The swiftly flowing waters of the Rio Negro poured through a gap in the rugged foothills of the Colombian Andes. Cold and muddy, it roared through the gorge, whipping itself into a white frenzy, angrily lashing out at the boulders clogging its depths.

Matt Castagna, 26, along with two friends, Paul Bartron, 18, and Bob Freeman, 28, worked their way upriver on foot, skirting the rocks and water. The three had come to Colombia with a team from SUMMIT, the short-term missionary program of New Tribes Mission. Comprised of teenagers and adults, the group was using their summer vacation to construct a duplex for housing missionaries. Castagna, along with his parents, Ben and Rita, were the team leaders.

Freeman was the calm and quiet type. He was serious and sensitive to his surroundings, be it nature or people and their needs. Bartron was a tease, he was the clown of the group. Vivacious and full of fun, he got along well with the others on the team. Different as they were, they liked fun and adventure and thus found themselves drawn to Castagna, who enjoyed a good time as well. He was well liked by people, and especially worked well with teens.

Ignoring a warning that the river was too dangerous, the three had spent the otherwise drowsy Sunday afternoon shooting the rapids in inner tubes. Now they were headed home–their bodies tired, their hearts laughing. Tubes draped over their shoulders; they picked their way through the rocks on the river’s edge. Their only other essentials for that afternoon of fun were tennis shoes and cut-offs.

It was a long way back to the trail where they had descended into the river gorge just a few short hours before. They wanted to get home sooner than later, and their eyes began to search the verdant slope, that rose hundreds of feet above them, for a way up and out of the river canyon. The dense subtropical growth seemed to block all exits.

They were elated when they found what they hoped was a shortcut to the top. It was a scar where nature, in a past moment of fury, had struck the earth, ripping her coat of green, exposing her nakedness, and all trees and underbrush had been swept away in the avalanche of dirt and rock thundering down the slope.

The humid breath of the tropics hung heavy around them. The exertion of climbing, mingled with the mugginess of the air, made their bodies melt. Their skin glistened with sweat. Breathing came in deep, full gulps. The men were thankful for helping hands, roots abandoned in the wake of the landslide gave them something to hang on to. Slipping and sliding, sometimes on all fours, they pulled themselves upward. The clay beneath their feet was brown, laced with stones, slick with the ooze of daily showers. Their ascending feet occasionally kicked rocks loose and sent them bouncing down the hill behind them. The one responsible for disturbing the stone would yell, “Rock!” to alert those following of the danger.

As the summit was neared, a new strategy had to be worked out. The incline was so steep, it became impossible to climb and hang onto their inner tubes at the same time. They spread out on the slope. Bartron went first, then Freeman. Castagna stayed back holding all the tubes until the others were in position; then, one at a time, he tossed a tube to Freeman, who tossed it to Bartron. The relay completed, they all climbed higher and repeated the process, slowly gaining altitude.

Castagna flung a tube upward. It glanced off a rock. Freeman made a futile attempt to catch it. In dismay, the three watched it bounce back down the slope, away from them. They were only 40 feet from the top. Castagna said, “You guys go on. I’ll wait here and then go down and get the other one.” Bartron and Freeman continued their upward scramble, clutching the rubber tubes in their hands. Mindful of rocks rolling down, Castagna moved to the side–but not far enough!

As he climbed upwards, Bartron, still in the lead, unintentionally dislodged a large stone. He yelled, “Rock!” Freeman ducked out of the way. Castagna saw it coming straight for him and tried to gauge which way it was going to bounce, but it happened so fast he couldn’t move. His arms seemed to be glued to his sides. He saw the rock four feet above him, and then . . . nothing. The rock smashed into his head, just above the hairline.

Reality fled! With incredulous eyes, Bartron and Freeman watched, horror-stricken, as the momentum of the rock knocked Castagna over backwards. Like a corpse, he hit the dirt and rolled over and over. Small rocks danced with sadistic glee beside him, and raced ahead as if to ensure the path was clear all the way to the bottom. Castagna’s body rolled around a corner and out of sight.

In the dreadful silence that followed, the realization of want had happened registered in their minds. Freeman yelled to Bartron, “Go get help!” Throwing caution and self-preservation off the cliff in front of him, he plunged down the slope, slipping and sliding over salient mounds of clay and rock. Cut and bruised, his cut-offs and body soiled with mud, he slid to a stop about 250 feet from where he had started at the top of the ridge. His eyes surveyed the scene before him. Blood was everywhere! Castagna lay dead or unconscious, Freeman wasn’t sure which, but the nausea a in his own stomach and the lump in his throat told him he had better do something quickly!

Freeman knew he had to stop the bleeding. He took off his shorts to press into the gash in Castagna’s head. Realizing they were caked with clay, he dropped them and without hesitation peeled off his cotton

briefs and placed them over the bleeding gash. He applied direct pressure to staunch the flow of blood. The gashes on Castagna’s shoulders and numerous smaller lacerations would have to wait.

Castagna slowly regained consciousness. He knew he was hurt, but how badly? He felt miserable–like one waking up with a headache. A bad one! It was more than just his head, though. His whole body hurt! He probed the walls of his mouth with his tongue and found unaccustomed gaps. He spat out pieces of teeth mixed with blood.

As the initial trauma of what had happened to him began to wear off, Castagna felt river rocks pushing into his abdomen and stabbing his legs. His injuries had drained all vitality from his body, and he couldn’t move. He pleaded with Freeman to lend a hand and help him sit up in a more comfortable position. Freeman told him, “Just lay still, lay still!” He asked if Castagna could move his feet and fingers and the response was positive.

Meanwhile, Bartron had reached the mission airstrip which ran alongside the top of the ridge. He raced to the dorm. Team members were lounging here and there, playing games, writing letters, making the most of their day off. Bartron shattered their lassitude. Panic clutching his throat, he yelled, “Matt’s hurt! Need a doctor!! Call somebody!”

Castagna ‘s mother, Rita, was sitting with some of the team when Bartron burst in. Her first thought was, “Now, Paul, quit clowning!” She looked at him trying to catch his breath. She saw his sweaty body and the fear coruscating from his eyes and knew something terrible had happened to her son. This time Bartron was serious! She ran to get her husband.

The hospital in Villavicencio (a nearby town) was contacted by shortwave radio and put on standby. One of the girls grabbed a first aid kit. Everyone made a dash for the river. Within 20 minutes, people were arriving at the scene of the accident. Some started down the landslide, and again, rocks began to tumble. Castagna cringed as a rock bounced toward him. It careened off to the side and crashed into the brush.

A plan was outlined for carrying him out of the gorge. Not realizing the extent of his injury, Castagna said, “Just help me up, and I’ll walk up the hill!” Their rebuttal was laced with inappropriate nervous laughter as they replied, “You’re in no shape to do that!” They rolled him into a hammock, tied the ropes to a pole, and picked him up. The pole sagged. The hammock dragged. Discarding the pole, three or four people got on each side with one at each end. Gripping the hammock in their fingers, they began the long-haul home. The procession headed downhill, across the riverbed, and toward the trail.

Voices were filled with concern as those around him spoke of getting him to the city and into a hospital. Castagna began to realize that his condition was worse than he first suspected. Visions of quadriplegics filled his head, and thoughts of being an invalid for the rest of his life vied for control of his mind. Those carrying him stopped frequently to catch their breath. Though the pain was intense, he was conscience of the effort they were putting forth to help him. He hoped they were his rescuers, and not his pallbearers! Some of the girls took up a song. Most were praying. Some told jokes. They kept up a busy chatter to keep him awake.

They climbed a few steps, stopped, and regrouped. Others were enlisted to replace those who were tired. Finally, they had to join their hands underneath him to carry him up the slope. Castagna began to shake and say that he was cold–the dawn of shock. A blanket was placed over him. Others in the group took off their shirts and covered him with them. Colombian kids, not fully understanding what had happened, were eager to help and added their shirts to the pile. Castagna kept asking, “Who’s bumping my shoulder?” He was reassured, no one was there!

They carried him out of the canyon and loaded him into a Jeep. His mother watched through tear-filled eyes. She searched her husband’s face for some sign of reassurance. All he could say was, “It’s bad!” Inside, he was wondering if they would be taking their son home for his funeral.

The Jeep eased out onto the airstrip and headed towards the waiting airplane. There, they gently put him onto the plane and secured him to floor with seat belts. His father climbed in beside the pilot; the engine roared to life and the Cessna 206 was airborne. It was after 6:00. Normally, the airport in Villavicencio would be closed for the night. The team had radioed the tower and asked them to stay on for an emergency flight, but one never really knew if they would wait! It was a ten-minute flight. On arrival, Castagna was loaded into a Jeep and rushed to the clinic–20 minutes away.

No pain killers were given that first night. Castagna, his hair matted, his body chalked with clay, was placed in a bed. The possibility of his neck being broken kept the nurses from cleaning him up other than scrubbing his topside a little. A door was placed under the mattress to keep his body rigid.

The doctor on duty thought that a neurologist should be called. The only one in town did not have a telephone; so, taking leave of his duties, the doctor joined the missionary driving the jeep to go find him. The specialist was not at home but was finally located at a friend’s house and taken to the clinic. By now, Castagna was sick and vomiting blood. There was swelling at the base of his skull–he would have to go for X-rays in the morning. Twelve stitches closed the large gash in his head. His father and the missionary with the jeep were sent to fill a prescription. . . no easy task! It was Sunday, most places were closed.

Night dropped a cloak of black over the city. Lights flickered in the gloom and the town began to doze. Sleep, however, was not bestowed on Castagna. His father stayed in the room, waking him, making sure did not lapse into a coma. Glucose and antibiotics dripped down a plastic tube and were silently assimilated into his bloodstream.

Monday morning dawned gray and weeping. Castagna was placed on a hospital cart and wheeled out the door and into the rain. An umbrella was held over his head. The cart dropped over the curb and turned down the cobblestone street. The wheels bounced over the stones. The trundle of the cart over the wet stones mingled with the soft patter of rain. Damp, but still intact, Castagna was placed on the X-ray table. X-rays over, he was pushed back to his room.

At night, his father kept watch by his bedside. During the day, his mother kept him company. His condition was still uncertain, but she was encouraged as she watched the strong palpitations of his heartbeat in his neck. On Tuesday, using all the Spanish she knew, supplementing with pantomime, she asked for clean sheets, a bowl with water, and a washcloth. After cleaning a little more sand and clay off her son, she changed the sheets. At mealtime, she placed a bib under his chin, across his chest, and spoon-fed him soup and rice.

Next morning, concern welled within her heart as she entered the room and perceived no pulse in his neck! At the same time of her arrival, the nurses entered the room to take his vital signs. They were laughing and talking. As fingers probed for the pulse in his wrist, they became frantic, all gaiety fled. Chatter subsided! “Forty-three. Impossible!” They ran to summon the doctor. Castagna’s mother was so distraught she began to speak in English. Frustration and a sense of helplessness overwhelmed her as she sought answers from uncomprehending faces. Her son’s condition was critical!

She kept her vigil at his side. Fear and worry, only natural emotions for a mother, filled her mind. She tripped over the “What ifs?” ” What if he’s not all right?” “What if he is paralyzed?” “What if he…She forced the thought of death out of her sphere of concentration. A spider climbed the wall above her son’s head. She swatted it. Its crumpled body fell to the floor. Not long afterwards, a patrol of ants hoisted it in their jaws and carried it away. She hoped that wasn’t a bodement of what would happen to her son.

By Wednesday, word of his accident had reached the States. New Tribes Mission as well as many churches across the States were notified. People began to pray. By that afternoon, Castagna began to mend. His vital signs normalized. He began to gain strength. The doctor said he could get up if he continued to improve. His father flew back to the mission base to again take charge of the team.

It was inexplicable…unless one believes in God and the power of prayer. The prescribed treatment of keeping him still was unaltered. No miracle drugs were given. There was even dissension among the doctors as to what was causing the problem. The X-ray technician believed there was a hairline crack in Castagna’s neck. The neurologist said it was a severe head injury. The X-rays were sent to the capital city of Bogota by taxi to solicit another opinion. The specialist there sided with the neurologist. The verdict–a fractured skull!

On Thursday, Castagna lay in his hospital bed. His mother wrote letters as he dictated them. He addressed himself to Paul Bartron, encouraging him to cheer up and not blame himself for what had happened. It was not his fault, and everyone was learning from the experience. To the others on the team, he wrote, “God has really been good to me, and I know it hasn’t been coincidence the way He has worked things out. I want to thank you all for your help in getting me to the airplane and for your continued prayers. Keep praying for me in the days ahead that I’ll be patient with the healing process of just resting. I really do thank the Lord for each one of you.”

He was in good spirits. The nurses came in laughing and giggling, again. They liked this tall gringo with the blond hair and blue eyes. They enjoyed it when he tried to talk with them in Spanish. He also practiced his Spanish when he joked with the little boys who, like bees, hurried up and down the halls, poking their heads into the rooms. Some barefoot, all dirty, they carried little pots of stew, rice, meat, and for a few pesos offered their specialties for sale. Though he would like to help them, he had to refuse. His broken teeth made it painful to chew. The hospital fare of beef, rice, and potatoes he also rejected, subsisting on soup from the hospital tray and milkshakes and eggnogs brought to him by his mother.

His ordeal was over. It still did not seem real, but the initial shock was gone. Had he slept in the night? He did not remember, but he did notice that the incessant blare of music from the cantina across the street had at last subsided. Sometime in the early hours before dawn, Castagna left his bed, hoping to find more comfort in the overstuffed chair in his room. It sagged beneath his weight, yet he hardly noticed the frame digging into his neck and the back of his legs. It was better than the bed! With disdain, he looked at the mattress where he had lain for five days. His muscles craved action; but the doctor had ordered three more weeks of rest, but not in that bed!

Dawn’s soft light slowly poured through the windows filling the room with pale light. How plain this place was! Yet, though humble, it had played a significant role in saving his life and speeding his recovery. How familiar it had become. A toilet and shower hid themselves behind a partition. Iron bars covered the two windows, not to keep patients in, but to keep thieves out. A small cupboard clung to the wall between them. His bed, a table, and the chair broke the monotony of the generic brown tile floor. A broken bottle stood watch in the corner. Castagna wasn’t sure why it was there.

He looked at each object in turn. This was his goodbye. He knew he wouldn’t miss any of them! Soon his parents would come to take him away. He placed a hand on his brow. Gently, his fingers moved upward through his hair. The slight pressure he exerted penetrated the dressing but did not inflict pain. He traced the gash that had split his scalp from forehead to crown. He knew it was only by the grace of God that he was alive! He didn’t know the reason God had allowed the accident, but he knew his Heavenly Father was there when the rock smashed into his head. He knew his Heavenly Father had been there every inch of the way as he tumbled down the mountainside. It was a good feeling to know his life was in God’s hands!

END

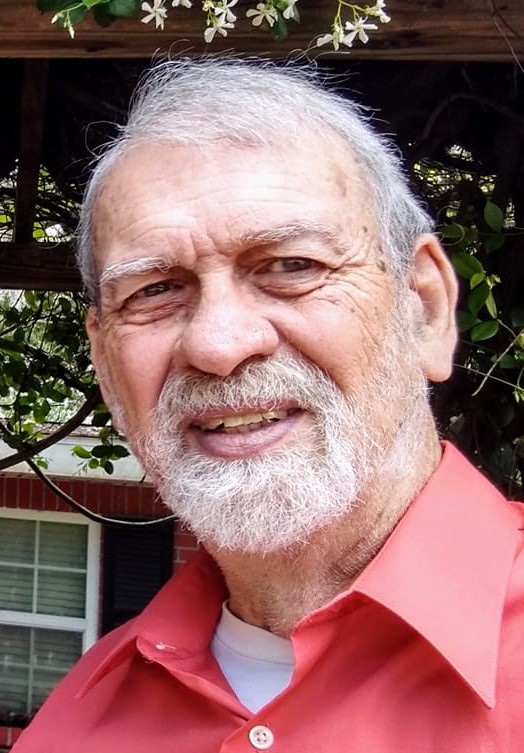

This story took place over 43 years ago. The ordeal happened to Matt, but he asked me a favor, to write it down on paper. He gave me a cassette tape with his recollections of his accident. Wanting to get more details and especially the emotions of the moment, I interviewed both his mother and father.

The idea was that we would sell the story to Reader’s Digest for their “Drama In Real Life” feature. We would split the money if the magazine bought the manuscript. My mission-received support in those days was usually less than $200 a month, so even if I got half of what RD would pay for a featured article it woud make me feel rich, at least for a few months! Over the next three months I poured my heart and soul into writing, probably spending upwards of 100 hours crafting the story onto paper. In those days there were no computers, and I didn’t even own a typewriter, so the initial drafts were written by hand. When I joined SUMMIT staff in 1981, headquartered in Kentucky at the time, I was able to use a typewriter and that sped things up a bit, even with my “hunt and peck” style of typing.

In the end, it was all for naught. Reader’s Digest rejected the story, saying only that it did not meet their editorial needs at the time. Hence, it lay at the bottom of a trunk, and later, in a file in my desk drawer for more than 40 years. I even forgot many of the details of what went down in those long-ago days.

Of course, all that came back when I dug it out last week and started to read and edit it, again. I had Matt’s permission to post it on my blog. I rewrote some of it. In the original finished manuscript, I gave too much credit of all that transpired that day to Destiny and Fate. They’re twins, and not always bad ones, but if we really believe that, as believers, we are in God’s hands, that He cares for us, that He is not going to give us more than we can handle, that He is working all things out for our good, and that He works through the natural laws that govern our fallen world, like gravity, then we can’t blame the bad things that happen to us on those malevolent siblings. We shouldn’t blame them on God, either! Bad things happen to us! We get down, discouraged and depressed. We feel pain in our bodies and our soul, We experience anguish of heart, sickness and even death.

God allowed Job to go through a lot. He lost everything, including his family. Yet, he declared, “Though He (God) slay me, yet will I trust Him!” In the end, God restored him and everything he had, better than it was before. When we keep believing in the One who wants the best for us, then fate and destiny (now they are good twins), bring us to a better place than where we started. Why? Because God is now in controll! The restoration may happen in our lifetime, or we may have to wait until we reach “that bright land to which we go.” Job was a better man, his faith stronger, because of what God allowed him to go through. I think Matt would agree the samed thing happened to him, too!

Psalms 66: 10-12 For You, O God, have tested us; You have refined us like silver. You led us into the net; You laid burdens on our backs. You let men ride over our heads; we went through fire and water, but You brought us into abundance.

Leave a comment